St. Basil’s Cathedral and the Triumph of Ivan the Terrible

Fairy tale, Disneyland, candy shop – these are the phrases you frequently hear people use to describe their first impression of St. Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow. It’s not hard to understand why. The design of the Cathedral, with all its colors and swirls, seems whimsical. Against the backdrop of the Kremlin’s red towers and the bright façade of GUM, St. Basil’s feels like the crown of some fantastical kingdom. You may be surprised to learn that this fairy tale is one of the most enduring legacies of Russia’s first Tsar, Ivan IV, better known as Ivan the Terrible. Intellectually gifted, Ivan IV ensured every element of St. Basil’s Cathedral was imbued with meaning. It is a physical manifestation of an idea that motivated him throughout his life and which led him to proclaim himself Emperor of the new Rome and protector of the Orthodox Christian faith.

The First Tsar

Born in 1530, Ivan IV had a tortured childhood. His father, the Grand Prince of Moscow, died when he was three and his mother when he was eight. After the death of his mother (who many believe was poisoned), a group of noblemen took charge of Ivan’s upbringing. These noblemen – the Boyars – terrorized and harassed Ivan, attempting to cow him into submission. That ended when Ivan turned 13 and ordered the worst of his tormentors arrested and fed to a pack of wild dogs. Though brutal, the act proved decisive in establishing his supremacy and securing his throne.

Upon his coronation, Ivan took the title Tsar (a Russification of Caesar), eschewing the traditional title “Prince”. This reflected a growing conviction within Russia that with the fall of Constantinople to the Turks, Moscow was now heir to the legacy of ancient Rome and the center of Orthodox Christianity. As Constantinople had been the second Rome, now Moscow would be the third, or so Ivan believed.

After assuming the throne, Ivan immediately began work to make this vision a reality. He began by looking east. For over a hundred years, Moscow had been fighting wars with the Khanate of Kazan (an Islamic successor state to the Mongol Golden Horde). Ivan was determined to end it. He worked to isolate the Khanate diplomatically and, once that was achieved, led an army of 150,000 soldiers against it. His army quickly fought its way to the city of Kazan, besieging it in late August 1552.

This was the tenth time Russian forces had besieged Kazan. It would also be the last. Aided by 150 siege cannon and an English engineer, Ivan breached the enemy fortifications in October and captured the town.

To the Russian people, the Kazan Khanate had become the embodiment of a devastating Mongol invasion that had begun 300 years before. At only 22, Ivan had decisively defeated it. On his way back to Moscow, he was greeted with even more good news. His wife had given birth to a son who they named Dmitry. On top of the world, the young Tsar ordered the construction of a new church outside the Kremlin in celebration of his victory. This church was the seed of what would one day become St. Basil’s Cathedral.

Tragedy and the Remaking of St. Basil’s

But it wasn’t St. Basil’s yet. It would take nine years and multiple iterations before St. Basil’s would take its present shape. It began as a small lone wooden church hastily erected in late 1552. This was replaced by a stone church in 1553.

It was around this time – in March 1553 – that Ivan grew seriously ill. Anticipating death, he asked the boyars to swear loyalty to his infant son. To his surprise, some at first resisted. Though all eventually came around, Ivan began to feel his dynasty’s position was more precarious than he had originally thought.

After recovering from his illness, he and his family went to Suzdal to pray at the Convent of the Intercession. On their way back to Moscow, Ivan’s infant son, Dmitry, died. The official history records that both Ivan and his wife, Anastasia, were devastated. This was their third lost child in three years, two infant girls having died before Dmitry was born.

The couple fervently prayed for another child and in 1554 their prayers were answered. In March of that year, Anastasia gave birth to another son who they named Ivan. Ivan (the father) was overjoyed. Historians speculate that it was the sense of triumph after years of personal struggle that moved the Tsar to re-examine his cathedral.

Protector and Disseminator of the One True Faith

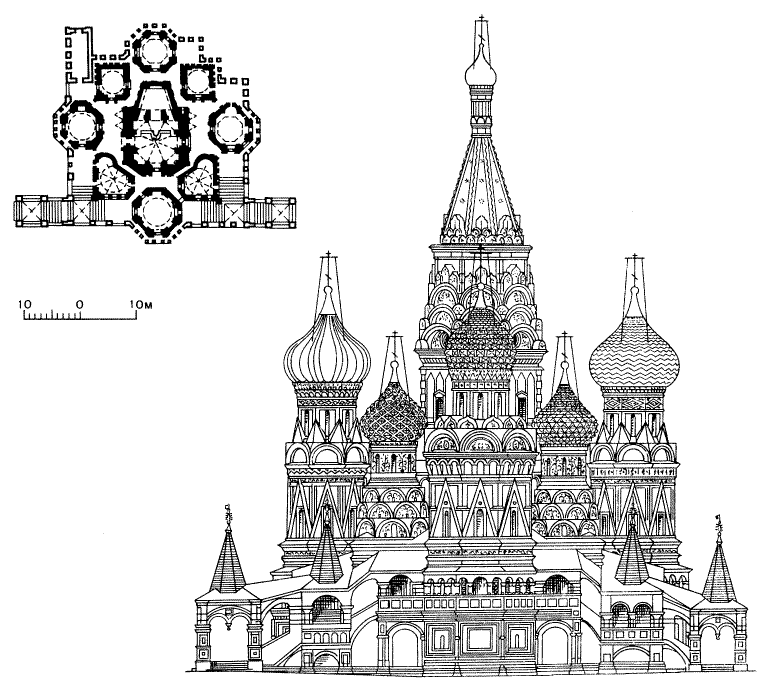

In 1555, Ivan hired two architects, Postnik and Barma, to revisit the design of St. Basil’s. With input from Ivan and the Metropolitan (the head of the Russian Orthodox Chruch), Postnik and Barma planned a structure with nine stone chapels on top of a single base. This modular design is the St. Basil’s we see today.

In making their design, Postnik and Barma were said to have incorporated elements from both traditional Russian architecture and innovations then being made in Italy, which was then in the High Renaissance. They were also said to have drawn inspiration from the Book of Revelations and its description of the Heavenly City:

And he that sat was to look upon like a jasper and a sardine stone: and there was a rainbow round about the throne, in sight like unto an emerald. And round about the throne were four and twenty seats: and upon the seats, I saw four and twenty elders sitting, clothed in white raiment; and they had on their heads crowns of gold.

— Revelation, 4:3–4 (KJV)

The intuition of many that St. Basil’s looks like something out of a fairy tale turns out to be correct. It was designed to appear not of this world.

Meaning and symbolism were woven into every aspect of the new cathedral. Each of its nine chapels was dedicated to a specific saint or event connected with Ivan’s Russia. The central chapel, for instance, was dedicated to the Intercession, which commemorates events in both Byzantine history and Ivan’s own conquest of Kazan.

The Byzantine Intercession venerates a vision by Saint Andrew the Fool. When Constantinople came under siege by Muslim Saracens in the tenth century, Saint Andrew and his disciples were said to have witnessed the Virgin Mary enter their Church, pray before their altar, and spread her veil over all within. This was taken as a sign of Mary’s protection. When the Byzantines later managed to successfully break the Saracen’s siege, the cult of the Intercession was born.

Ivan saw parallels between this event and his own successful conquest of Kazan. During this campaign, one of Ivan’s soldiers was said to have had a vision of Saint Nicholas, who told him that the attack on Kazan should begin immediately. Ivan followed this advice and emerged victorious. By dedicating St. Basil’s primary chapel to the Intercession, Ivan was making a statement that he, like the Byzantine Emperors who preceded him, benefitted from divine favor.

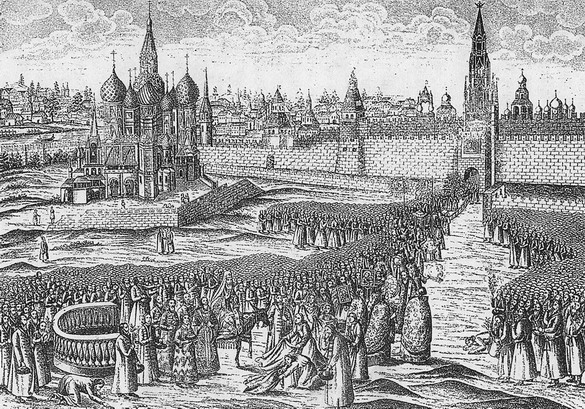

The eight side chapels further reinforce this message, memorializing key battles in Ivan’s campaign against Kazan and the dynasty’s connection to God. The largest side chapel was dedicated to the “Entry into Jerusalem,” which as the name suggests, commemorates Jesus’ entrance into Jerusalem on the back of a donkey. This chapel became the focus of a Palm Sunday tradition begun under Ivan, whereby the Tsar, on foot, led a horse from the Kremlin to the chapel. On the horse rode the Metropolitan, symbolizing Christ. Here again, St. Basil’s played a central role in a ceremony meant to represent Ivan’s bringing Christ to the unbelievers, as he had supposedly done through his capture of Kazan.

Reigns of Terror and Times of Trouble

Construction of St. Basil’s Cathedral finished in 1561. Over the years, surprisingly few changes were made to the Cathedral. Visually, the most notable change was perhaps the coloring of its onion-shaped domes. Originally, the domes had been white, red, and gold. Blue, green, and other colors were later added as new pigments and dyes became more widely available. Structurally, the most important addition to the Cathedral was made in 1588, when a tenth chapel was added to commemorate Saint Vasily the Blessed, known outside of Russia as Saint Basil (from which the present church takes its name).

The completion of St. Basil’s in 1561 was in some ways the high point of Ivan’s reign. Following the annexation of Kazan, Ivan conquered the Khanate of Astrakhan, adding its territories to his growing empire. His achievements on the domestic front were no less impressive. Among his most notable accomplishments was the completion of an ambitious series of legal reforms and the establishment of a professional standing army. Russia was now a serious power in a way that it had never been before; and Ivan’s vision of Moscow as a third Rome no longer seemed so farfetched.

And it was at this point that Ivan, by his own hand, began to undo it. He established a personal guard, the Oprichniki – considered the forerunner of Russia’s modern intelligence services – and unleashed them on his own people in a campaign of state-backed terror. He razed the ancient and prosperous city of Novgorod (the second largest city in Russia at the time) to the ground, torturing and killing thousands of people from all classes and backgrounds. He launched a 24 year war against his western neighbors, resulting in a stalemate and bankrupting the young Russian state. And, perhaps the deed he is most famous for, he beat to death his own son (and heir) in a fit of rage. Yes, the same son whose birth inspired him to expand Saint Basil’s into its present form. With the death of his son, Ivan’s mentally-challenged middle son, Feodor, became Tsar. Feodor’s reign led directly to the “Times of Trouble,” a 15-year period during which Moscow would be occupied by Polish invaders and Russia would near collapse.

Ivan IV turned out to be his own worst enemy, ultimately giving in to the paranoia and neuroticism that had plagued him for most of his life. In so doing, he sabotaged the survival of his dynasty and nearly destroyed the state he and his ancestors had worked so hard to establish. Yet despite the chaos and destruction Ivan left in his wake, St. Basil’s survived – its other-worldly beauty the sole remaining testament to a young Tsar’s grand vision of a third Rome.

Related Content

- For further information on the fall of Constantinople, see my post on the Grand Bazaar, available here.

- Moscow’s rise was substantially aided by the continued decline and fragmentation of the Mongol Golden Horde. Many of its successor states, such as the Khanate of Kazan, would eventually be picked off by a rapidly expanding Russia. To learn more about what sent the Golden Horde into decline, read my piece about Tamerlane – here.

- To read about another cathedral that would become closely associated with royalty, check out my post on Notre Dame, here.

Sources/Further Reading

- Flier, Michael S. “Filling in the Blanks: The Church of the Intercession and the Architectonics of Medieval Muscovite Ritual.” Harvard Ukrainian Studies, vol. 19, 1995, pp. 120–137.

- Shvidkovskiĭ, Dmitriĭ Olegovich. Russian Architecture and the West. United Kingdom, Yale University Press, 2007. (Excerpts available here)

- For further insights into Ivan’s character and vision, see this fascinating summary of an exchange between Ivan and an old friend who defected to the west: https://www.nytimes.com/1988/02/14/books/the-prince-and-his-czar-letters-from-exile.html