The Grand Bazaar and the Rebirth of Istanbul: A History

On the 29th of May 1453, Constantinople fell to the besieging Turkish army. The fall of the great capital of the Byzantine Empire to the Ottoman Turks is often depicted as a great tragedy for Western civilization. It had been Constantinople, after all, that had carried on the 2,000 year legacy of ancient Rome. But as they say, every ending is also a beginning. The Ottoman Turks would remake Constantinople (later Istanbul) into the center of a new empire, building on and even surpassing the achievements of those who had ruled the city before. Central to this was the establishment of the Grand Bazaar. The Grand Bazaar was the creation of a forward-thinking ruler who fully embraced a multiethnic and multicultural vision of empire. In so doing, he created a resilient institution that would go on to survive natural disasters, wars, and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire itself.

Continuity and Change in the Grand Bazaar

Few institutions can claim a longer historical lineage than the Grand Bazaar, which after 550 years is as vibrant as ever. It has of course changed significantly over the centuries. The shopkeepers of the Grand Bazaar no longer enjoy the special favor of their Sultan nor are most of them any longer directly involved in the production of the goods they sell. However, to the 26,000 people who work at the Bazaar, there is still a sense of connection to those who came before.

This continuity is visible in the traditions and organization of the market itself. As in the past, stores selling similar items cluster together along the same street. Serving tea is still a common tactic to create a more intimate environment in which a deal may be struck. And while some stores sell only cheap touristy trinkets, others trade in carpets, ceramics, and artisanal jewelry rivaling the quality available anywhere in the world.

These shops are also palpably connected to the past through the physical space of the sprawling market. The wide halls topped by domes and arched windows, some painted with dramatic gold and blue trim, were built over centuries. But like a person changes as they grow older, so too has the Grand Bazaar. And these changes go deeper than just the addition of the now ubiquitous neon and LED signs. Over its history, the merchants of the Grand Bazaar have had to contend with near constant change, ranging from the industrial revolution and the collapse of the Empire, to the more recent the rise of the modern shopping mall and the growth of the digital economy. Yet through these 550 years of near constant, sometimes earth shattering changes, the Grand Bazaar remains an important commercial center. The source of its resilience lies in the reign of Sultan Mehmed II, also known as Mehmed the Conqueror. He leveraged the knowledge and skills of diverse peoples to give new life to an imperial capital deep in decline. In so doing, he laid the foundation for a bazaar that would generate untold levels of wealth and which would survive some of the greatest changes in human history.

The End of the Roman Empire

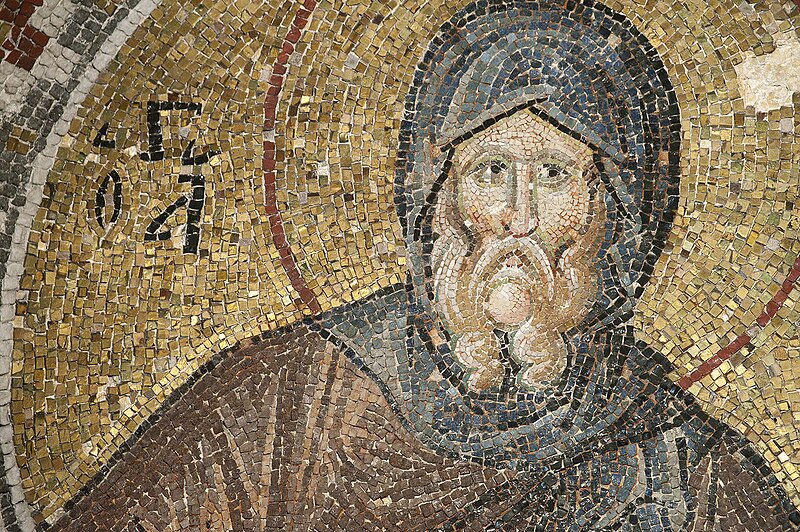

As the Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca once said, every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end. The beginning of the Grand Bazaar is inseparable from the history of the city of Istanbul, which before being captured by the Ottoman Turks, was the capital of the Byzantine Empire. The seeds of what would become the Byzantine Empire were planted in 330 AD, when the Roman Emperor Constantine I moved his capital from Rome to Byzantium, renaming it Constantinople. Constantine had chosen one of the most strategic locations on Earth for his new capital. Located on the Bosporus Straits, the city controlled the only link between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. From this location, the Empire’s armies, merchants, and religion could be easily dispatched into the heart of Asia, Africa, and Europe. The Byzantine Empire’s control over this strategic location and the trade that flowed through it was one of the key factors that made it the most powerful state in the region for much of its history.

After reaching its apex in the 11th century, the Byzantine Empire began to slowly decline. Ironically, the greatest blow to the Empire was dealt not by Muslim invaders, but rather its Christian neighbors. In 1204, a crusader army sacked Constantinople, establishing a short lived “Latin” kingdom. This fractured the empire into three smaller successor states, one of which later recaptured the city. Further civil wars provided an opening for rising powers in the east (most notably the Ottomans Turks) to advance west. Over the course of the 14th century, the Turks went on to consolidate their control of Asia Minor and make inroads into Europe. With the loss of its hinterland and the devastating “Black Death” in the mid-fourteenth century, the population of Constantinople declined dramatically. By 1453, when the armies of Sultan Mehmed II finally took the city, it had a population of between 30,000 and 60,000 people, a shadow of its former past.

Mehmed II had long made it his mission to capture Constantinople. His father, Sultan Murad II, had nearly captured the city himself over thirty years earlier, but had to abandon the siege to deal with an internal rebellion initiated by his brother. When Mehmed turned his sights on the city, he faced no such distractions. He first took control of the Bosporus by building new fortifications around the Strait. This gave him control of the city’s trade and prevented the arrival of reinforcements from the north. He then moved his army of 50,000-80,000 men against the city, which was defended by an army one-tenth the size of his own. The city held out as long as it could, but finally fell on the 55th day of the siege. Following its capture, the Sultan allowed his soldiers to plunder the city for three days, after which he began to build.

Mehmed’s Vision and the New Byzantium

Mehmed II was no ordinary monarch of his age. He is reported to have spoken five languages, including both Greek and Latin. He was acutely aware of Constantinople’s legacy as heir to over 2,000 years of Roman civilization. In taking Constantinople, he intended not only to continue this legacy, but to build on it. This included maintaining most of the Byzantine Empire’s administrative institutions, such as those overseeing customs and tax collection. He even gave important administrative and military positions to the last Byzantine Emperor’s nephews, one of whom had been next in line of succession. One of these nephews would go on to serve twice as Grand Vizier (roughly the equivalent of Prime Minister) under Mehmed’s son.

Mehmed’s most important work, however, was the renewal of Constantinople (later Istanbul) itself. As noted above, the city’s population had fallen drastically over the centuries. Mehmed was determined to bring it back to its former glory. To ensure the remaining population of tradesman and merchants didn’t leave, he issued decrees protecting their property and promising not to force them to convert to Islam. When persuasion didn’t work, Mehmed was not averse to using coercion. He forcibly relocated groups of individuals from across the Ottoman Empire to Istanbul, settling them in districts within the city based on their ethnicity. As a result of these actions, by 1507, Istanbul’s population had increased to 350,000-400,000, making it the most populous city in the world – a position it would hold for over three centuries until being surpassed by London in the middle of the nineteenth century.

The Grand Bazaar and the Seeds of Prosperity

As the city’s population rebounded, Mehmed channeled the energies of the city’s inhabitants to achieve new heights of economic and cultural production. The tool he used to accomplish this was the Grand Bazaar. In 1456, Mehmed ordered the construction of a bedesten (the Turkish word for a building housing a market) in an abandoned area of the city. This bedestan, called the Cevâhir Bedestan (the Bedestan of Gems), would eventually become the core of the Grand Bazaar. Another bedestan, the Sandal Bedestan, would be built shortly after as trade expanded. As the bedestans reached full occupancy, tradesmen and merchants began to set up stalls in the surrounding streets. These shops, originally wood, would eventually be replaced with brick and stone buildings and the streets between them covered – thus forming what we know today as the Grand Bazaar. Eventually, the Bazaar would incorporate 61 streets and cover a total area of 30.7 hectares.

Though the center of commerce in the city, the Grand Bazaar provided more than just a place to do business. It also played a key role in financing important public services. Merchants seeking to set up shop in the Grand Bazaar had to pay a fee to the pious endowment of the Hagia Sophia – the central cathedral of Constantinople which was converted to a mosque after the city was captured. The fees collected by the endowment were used to set up schools, soup kitchens, and hospitals, providing essential services to the city’s inhabitants. It is estimated that the goods and services provided by theses endowments accounted for 80% of all consumption in the city. In this way, the Grand Bazaar played an instrumental role in ensuring the basic needs of all who resided in the city were met.

The Grand Bazaar was also at the heart of Ottoman cultural production. Leading craftsman from the bazaar were recruited into the prestigious Corps of Court Artists. As the name suggests, members of the Corps of Court Artists were entrusted with providing the material artifacts that filled the Sultan’s palaces. Jewelry, carpets, paintings, clothing, and ceramics were all furnished by the Corps of Court Artists. The craftsman who made up this institution were given broad discretion over their productions and enjoyed high compensation and special sumptuary privileges through their relationship to the court. Once items were accepted by the Sultan, these craftsman could provide similar items to their private customers at the Grand Bazaar. In this way, court culture made its way into broader society, generating both a unique and broad cultural identity.

The Trade Continues

Up until the 19th century, the Grand Bazaar offered goods of unparalleled quality and variety, bringing a high level of prosperity to Istanbul. But 350 years after its founding, the fortunes of the Bazaar began to turn. In the 19th century, Western Europe entered the industrial revolution, eroding the cost advantages of Ottoman guilds. This was further exacerbated by the 1838 Treaty of Balta Liman, in which the Ottoman Empire fully opened its domestic market to British trade. Reforms were attempted, but none succeeded in arresting the long-term decline of key Ottoman industries and the Grand Bazaar’s centrality in international trade.

Though no longer the trade hub it once was, the Grand Bazaar nevertheless remains both an important center of commerce and a world-renowned tourist destination. Before COVID-19, millions of people visited the market every year, drinking tea with store proprietors as they haggled over the price of a carpet, or jewelry, or a leather jacket. These visitors will undoubtedly return once the pandemic is over, seeking to both strike a deal and feel a connection to its storied past. In this, shoppers and store owners alike carry forward a tradition that opened new possibilities for generations of people and without which, the modern city of Istanbul would not exist.

Related Content

- Byzantine Constantinople was not the Ottoman Turk’s only enemy. In fact, a rising power to the east proved to be a far greater threat, halting Ottoman expansion for decades. Read about it, here.

- The fall of Constantinople had a profound impact throughout the Orthodox Christian world. This was particularly the case in Russia, where Ivan the Terrible proclaimed Moscow to be the Third Rome. To learn more, see my piece on the topic, here.

Sources/Further Reading

- Kenan Mortan and Önder Küçükerman, Istanbul and the Grand Bazaar, trans. J.H. Matthews (Istanbul: Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture, 2009)

- Sardar, Marika. “The Greater Ottoman Empire, 1600–1800.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000 (available here)

- Yildirim, Onur. “Ottoman Guilds in the Early Modern Era.” International Review of Social History, vol. 53, 2008, pp. 73–93