The Bronze Age Collapse: The Fall of the First Globalized Era

Imagine the world is rocked by a series of simultaneous cataclysms – earthquakes, drought, war, famine. Civilization as we know it completely collapses. Infrastructure falls to ruin, historical records are destroyed, and the populations of entire nations are lost and scattered. That could never happen, right? Well, according to Eric Cline, it has. In his book, “1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed,” he paints a vivid picture of an ancient world of powerful and flourishing empires. Connected through trade and diplomacy, the great powers of this age reached unprecedented heights of prosperity and cultural sophistication. Then, within a few decades, it all disappeared. Today, we refer to this period as the Late Bronze Age and the causes for its sudden collapse are still the subject of heated debate.

The First International Order

Originally published in 2014, Cline’s history of the Late Bronze Age has attracted quite a bit of attention in recent years. The story starts in about 1500 BC, with the emergence of a new historical order in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean. Cline characterizes this age as possibly the first truly international world to ever exist – at least on this scale. It involved a panoply of powers – the Hittite Empire based in Anatolia (modern day Turkey), the New Dynasty of Egypt, the Myceneans in mainland Greece, the Kassites in Babylonia, the Cypriots, Minoans, Caananites, and many others.

Archeological and textual evidence from the period documents extensive contact between these civilizations – particularly between rulers. Royal correspondence shows rulers discussing everything from alliances and peace treaties to royal marriages and the exchange of gifts. The exchange of gifts seems to have been a particularly important preoccupation of the kings and queens of the age. Cline cites one letter from Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten which includes a 300-line list of gifts sent to the King of Babylonia. This list includes gold, silver, and bronze objects, an array of jewelry, perfumes, rich textiles, thrones, mirrors, and many other objects of value. Often, gifts would include artisans – such as sculptors, masons, and skilled laborers. These artisans brought their home cultures to new lands, introducing their hosts to new ideas and artistic styles. The proliferation of Aegean-style wall paintings throughout the Eastern Mediterranean is one example of how elements of different cultures diffused throughout the region.

The Great Powers of the Bronze Age: The Egyptian-Hittite Rivalry

Of course, as in any age, contact between major powers occasionally resulted in conflict. So it was with the two most powerful kingdoms of the Late Bronze Age – the Egyptians and the Hittites. These two powers had a relationship akin to the United States and Soviet Union during the Cold War. They were in frequent conflict, either directly or through proxies, constantly trying to outflank each other diplomatically and militarily. Much of the drama played out in the Eastern Mediterranean, around modern day Syria and Lebanon. One particularly notable conflict was the Zannanza Affair. The Affair began when the Hittite King Suppiluliuma (likely the most successful Hittite King ever to rule) received a strange letter from the Egyptian Queen Ankhsenamun. The Queen’s husband – the famous Tutankhamun, better known as King Tut – had died unexpectedly, leaving behind no heirs to succeed him. In the letter, the Queen asks Suppiluliuma to provide a son for her to marry, promising that this son would become Pharaoh over all of Egypt.

Suppiluliuma was suspicious – Egypt had traditionally refused to marry off female members of its royal family to foreigners. But after some further back and forth with an Egyptian envoy, Suppiluliuma accepted Ankhsenamun’s offer, sending his son Zannanza (the fourth eldest of his five sons) to marry the queen. Unfortunately, Zannanza would not become pharaoh. His party was ambushed en route by an unknown group of assailants and Zannanza was killed.

Suppiluliuma was furious, believing that the whole affair had been a nefarious plot by the Egyptians. He attacked Egyptian cities in southern Syria, capturing a number of Egyptian soldiers. Unknown to the Hittites, a plague had been spreading through the Egyptian soldiers’ ranks. When the Hittites brought back the captured soldiers, they also brought back the plague that had been afflicting them. This plague would hit the palace hard, ultimately taking the life of Suppiluliuma and many other members of the royal family. It did not, however, end the tension between the Egyptians and the Hittites.

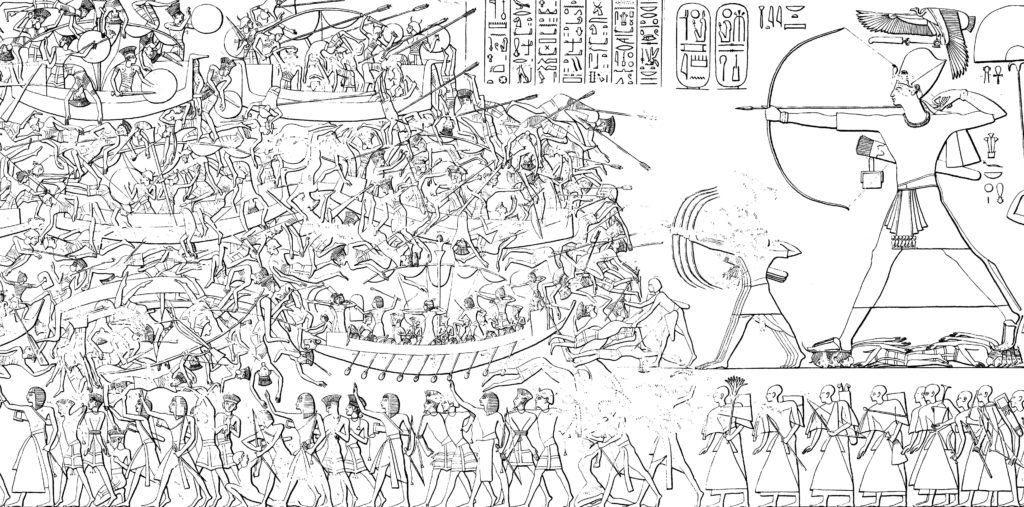

Bronze Age Heroics and The Battle of Qadesh

50 years after the Zannanza affair, conflict would again break out between the Egyptians and the Hittites. This war would culminate in the Battle of Qadesh in 1274 BC. According to Cline, the Hittites under Muwattalli II were attempting to expand further south into areas traditionally controlled by Egypt. The Pharaoh Ramses II moved to check Hittite expansion, leading four divisions to the border at Qadesh, near the modern Syrian-Lebanon border.

As the Egyptian forces approached the city, they captured two Hittite spies, who revealed that the Hittite armies were still far to the north. Ramses II took his Amun division and sped to Qadesh to secure the city before the Hittites arrived. Encountering no resistance, they made camp just to the north of the city. There, they captured two more Hittite spies, who revealed that the Egyptians had walked right into a trap. The Hittite forces were not only already in Qadesh, their army was hiding beneath the city walls. As the second Egyptian division passed the city, the Hittites sprung their trap. The entire Hittite army crashed into the Egyptian division, annihilating it. They then turned and engaged Ramses and his troops, this time meeting stronger resistance. An inscription on an Egyptian temple wall offers an account from Ramses of this pivotal moment in the battle:

I found Amun came when I called to him,

He gave me his hand and I rejoiced

…

I shot on my right, grasped with my left

…

I found the mass of chariots in whose midst I was

Scattering before my horses

I slaughtered among them at my will.3

While Ramses II probably did not single handedly hold off the entire Hittite army, his division did successfully hold them in check until the rest of the Egyptian army arrived. The battle ultimately ended in a stalemate. Shortly after, the two sides concluded a peace treaty (known as the Silver Treaty), keeping the border fixed at Qadesh.

Drought, Famine, Earthquakes, and Sea Peoples – The End of the Bronze Age

These are just some of the events of the Late Bronze Age for which records survived. Reconstructing other major events that are believed to have occurred during this time period – most notably the Trojan War and Exodus – have proven far more difficult. Cline’s book details the challenges faced by archeologists as they try to piece together events of the Late Bronze Age. He notes that some settlements have been under excavation for decades, yet basic facts are still contested – When was a settlement occupied? Was it destroyed in a war or by an earthquake? Was the entire settlement destroyed or just the palace? These questions are often extremely difficult for archeologists to answer.

Which brings us to the biggest mystery of all – what caused the rapid collapse of civilizations in and around 1177 BC? Cline notes that for most of the last century, scholars have attributed the collapse of the Late Bronze Age civilizations to invasions by the “sea peoples”. This notion comes from an Egyptian account of an attack on Egypt around 1177 BC by a confederation of seafaring groups (whose origins remain uncertain). According to the Egyptians, the attack on their lands came after the sea peoples had already overrun a number of other kingdoms across the Eastern Mediterranean, including the Hittites. The Egyptians succeeded in repelling the invaders, but the battle marked a turning point for the New Dynasty and Egypt, which went into a decline from which it never recovered.

Cline notes that new archeological evidence is now challenging the belief that the Late Bronze Age collapse was entirely due to the sea peoples. For one, the Eastern Mediterranean appears to have been rocked by a number of other disasters in the decades both before and after 1177 BC. This includes a severe and prolonged drought which caused widespread famine. It also includes a number of earthquakes, which ravaged the region around the same time and hit mainland Greece particularly hard. These disasters likely prompted mass migrations (including perhaps by the sea peoples) which would have fueled conflict and cut off trade routes. In a globalized world like the Late Bronze Age, the loss of trade routes would have limited access to crucial commodities, such as grains and bronze, possibly creating an economic crisis. Cline argues that it was this confluence of disasters, some natural and some man made, which likely overwhelmed Bronze Age civilizations, leading to their collapse.

The Exploration Continues

Though Cline steadfastly argues for his hypothesis, he admits that further investigation is needed. Determining what exactly caused the Late Bronze Age collapse is an extremely difficult problem given the number of possible causes – sort of like determining which member of a firing squad fired the fatal shot. Adding some urgency to this investigation, Cline suggests many of the factors that likely led to the Late Bronze Age collapse (climate change, war, economic crisis) are present in society today. Could we be heading toward our own Late Bronze Age-style reckoning? I’ll let you decide for yourself.

That debate aside, what really pulled me into Cline’s book was his passion and admiration for the grandeur of the Late Bronze Age. It leaves you with the feeling that the greatest loss from this era was not the palaces of mighty kings or the fall of empires, but the loss of its history. It left me wondering how much more of the story is still out there, lying beneath the ground, waiting to be discovered.

Sources/Further Reading

- Cline, Eric H. 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014. Available for purchase, here.

- If you don’t have time to read the book, Cline has many lectures on youtube where he summarizes its key themes. One is available, here.

- The above account of the Battle of Qadesh by Ramses II comes from the Poem of Pentaur, which was inscribed on five different Egyptian temples. The translation above comes from, here. The source of the translation is listed as: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World’s Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. III: Egypt, Africa, and Arabia, trans. W. K. Flinders Petrie, pp. 154-162.

- The firing squad analogy above is frequently used to explain the idea of overdetermination. Cline is arguing that the collapse of the Late Bronze Age is not overdetermined – that is, no one factor (be it drought, famine, earthquakes, sea peoples) would have by themselves been sufficient to have caused the Bronze Age collapse. While he does not use this particular term in his book, I think it’s a useful way of thinking about the problem.

- The events of the Bronze Age continued to echo throughout history. 2,500 years after the Bronze Age collapse, Turkish Sultan Mehmed II claimed to have avenged the Trojans through his conquest of Istanbul. See my post on that, here.

- This is my second piece dedicated to the investigation of an ancient mystery. My first one on the Roman Cult of Mithras is available, here.