Basket of Fruit by Caravaggio: Finding Meaning in Still Life

At first glance, Basket of Fruit by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio seems entirely ordinary. If you saw it outside of a museum, you might imagine it was a simple ornament or maybe even a pattern on some old wall paper. The arrangement looks attractive enough, a bright red and yellow apple sits tantalizingly on top. Luscious grapes are piled high, spilling out of the basket. Figs peak out at odd angles. But as you look closer, something begins to feel amiss. You notice the prominent hole on the apple and other blemishes. The abundant foliage, still stuck to the stems, appears mottled and damaged. Among the plump grapes, you notice a few have begun to shrivel. You begin to hope that someone will eat this fruit before it goes bad. Basket of Fruit by Caravaggio clearly contains more than meets the eye. In this seemingly innocent still life is something subversive. That initial sense of joy is tainted by a consciousness of impermanence, a forewarning of imminent spoilage. This is the painting equivalent of the age old adage, “nothing lasts forever.”

The Long Road to Rome

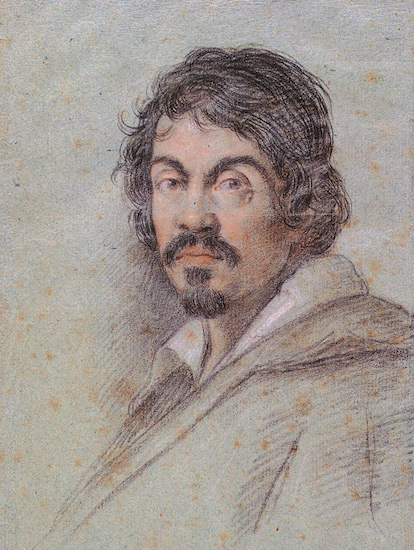

The late 16th/early 17th century Italian painter Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was the most innovative painter of his age, depicting sacred and classical scenes with a level of raw realism that had never before been seen in Roman art. He achieved this level of realism in part through the use of “still life” – the depiction of inanimate everyday objects. Caravaggio included still lifes in many of his most famous paintings, portraying an array of vivid, unadorned images: a carafe of flowers; a pile of clumsily stacked tools; a discarded sheet of music. And these weren’t mere decorations. They were critical elements of his compositions – so much so that he once remarked that it took him as much effort to paint “a good picture of flowers” as it did a human figure.

Despite his interest in the genre, Basket of Fruit appears to have been Caravaggio’s only stand-alone still life. It was a strange subject for a painter like Caravaggio to have chosen. Likely painted in the late 1590’s, it would have carried deep personal significance for Caravaggio. This was a period when the painter was just beginning to make a name for himself. He had come to Rome in the fall of 1592 after completing a four-year apprenticeship in his native Milan. After taking a range of odd painting jobs in Rome, he eventually found a position as a studio assistant to Giuseppe Cesari, possibly the most famous painter in the city at the time. During his time as a studio assistant, Caravaggio was tasked with painting “flowers and fruit” on the margins of Ceseri’s larger works. This put him firmly at the bottom rung of the painting hierarchy, well below those who painted animals, landscapes, and (most lofty of all) human figures.

Caravaggio would make repeated attempts to demonstrate to his employer that he was capable of much more, yet Cesari refused to let him paint anything else. Seeing no way forward, Caravaggio left Ceseri’s workshop to strike out on his own. It wouldn’t take long before others would see the budding talent that Cesari had missed. Eventually, his paintings would catch the attention of the powerful Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte – the Medici’s man in Rome – who for the next several years would be Caravaggio’s primary patron. Through del Monte’s patronage and support, Caravaggio would come to the attention of other Church leaders, winning a string of steadily more prestigious commissions. It was shortly after securing del Monte’s patronage that Caravaggio painted Basket of Fruit.

The Drama of the Everyday

It may seem a bit counter-intuitive that after finally being recognized as a painter of human figures, Caravaggio would return to still life – a genre most prominent Roman painters still felt was beneath them. Two factors may have motivated Caravaggio to experiment with the genre. First, still life would have allowed Caravaggio to further develop the style for which he would become best known – one that emphasized the relatable and mundane over the idealized and unattainable. The produce in Basket of Fruit is far from perfect, even showing signs of infestation. In 16th century Rome, such raw depictions of nature were frowned upon. An artist was to paint beautiful, idealized forms carefully arranged to illustrate sacred themes. Caravaggio’s paintings were a decisive departure from this insular view of art. Yes, we might say that an unblemished apple (or person) is more beautiful, but Caravaggio understood that it was the flaws that move us emotionally.

The second factor motivating Caravaggio’s return to still life may have been a growing conviction that in art, the line between still life and figures – objects and the human form – could be transcended. He understood that with careful composition and an eye for detail, the drama of one could become the drama of the other. In Basket of Fruit, we see a moment of ripeness captured just before an inevitable decay. Time grinds forward, bringing with it entropy and death. The leaves are first to go, but the rest will soon follow. The signs are already there. Time and decay – what more human theme could there be?

The Miracle in the Shadow

Still life would continue to be an important element of Caravaggio’s paintings for the rest of his career. Fruit in particular would make frequent appearances in Caravaggio’s art. One example is Boy Bitten by a Lizard, which was painted around the same time as Basket of Fruit. In this painting, a boy is depicted on the point of shrieking, having been bitten by a lizard as he reaches for a piece of fruit. Here the fruit – an assortment of cherries, figs, and grapes – is frequently interpreted as a reference to worldly pleasure with the lizard’s bite serving as a warning of the hazards inherent in its enjoyment.

Fruit would also make an appearance in Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus. This painting depicts a biblical scene following the resurrection of Christ. According to the gospels, two disciples encounter Christ on the way to Emmaus, but lacking faith in the reality of the resurrection, they do not recognize him. It is only when they sit for a meal and Christ blesses and breaks bread with them that recognition dawns. At this moment, Christ vanishes.

Caravaggio’s painting depicts the moment just before Christ disappears. The disciples sit down for their meal, still not quite able to believe in the miracle of the resurrection. The tavern keeper stands over them. On the edge of the table sits a basket of fruit, very similar to the one in Basket of Fruit. Here, the overflowing grapes likely contain a eucharistic meaning. From grapes come wine, which in turn is transmuted into the blood of Christ. The connection with Christ is further enhanced by the basket’s shadow, which resembles a fish. Taken together, the basket of fruit builds on the central theme of the painting – just like the mysterious guest, hidden in this fruit is the presence of the divine. The position of the fruit, situated precariously on the edge of the table, mirrors Christ’s imminent disappearance. One can imagine the basket striking the ground at the exact moment the two disciples recognize the young stranger with whom they are breaking bread. The disciples turn around to see what the commotion is, then turn back to see that Christ has disappeared.

Summing Up: Basket of Fruit by Caravaggio

Basket of Fruit by Caravaggio is most notable as an early example of the artist’s trademark naturalism. This gives the work a sense of authenticity, which resonates in a way that the more conservative depictions of beauty common in 16th century Rome rarely achieved. As a still life, however, it mostly went unnoticed. It was only when Caravaggio began to depict religious subjects with this same level of naturalism that the art community woke up to what he was doing. When these images of haggard men and women (often depicted in their moment of martyrdom) began to appear in the churches of Rome, the reaction was predictably intense and divisive. To Caravaggio, however, this was art. It didn’t matter if the subject was a basket of fruit or Christ himself, he was determined to paint what nature presented him with.

Sources/Further Reading on Basket of Fruit by Caravaggio

- For more information on Caravaggio, see this post on the artist’s life and most famous paintings.

- For more on how Caravaggio applied the same level of realism to his human figures, read this post on The Musicians.

- To read about how Caravaggio applied naturalism in his religious paintings, see this post on Adoration of the Shepherds.

- Swarzenski, Hanns. “Caravaggio and Still Life Painting: Notes on a Recent Acquisition.” Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts, vol. 52, no. 288, 1954, pp. 22–38.

- Graham-Dixon, Andrew. “Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane.” Allen Lane and Penguin Books. London. 2010 – A beautiful and very readable biography of Caravaggio. I highly recommend it.

- Warma, Susanne J. “Christ, First Fruits, and the Resurrection: Observations on the Fruit Basket in Caravaggio’s London ‘Supper at Emmaus.’” Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte, vol. 53, no. 4, 1990, pp. 583–586.

- Wind, Barry. “Genre as Season: Dosso, Campi, Caravaggio.” Arte Lombarda, no. 42/43, 1975, pp. 70–73.

- Impermanence is a common theme in art across many media. For poems on impermanence, see Frost, Shelley, and Keats.